Every trip requires preparation, but the level of prep can vary greatly. For our upcoming trip to Botswana, there were many more checkboxes on our pre-trip to-do lists than typical.

One example was that at the top of the packing list, it reads “pack lightly, max 15 kg”. However, kind of like when a parent tells you to do something, it doesn’t really hit home until you hear it from another source. In this case, my second opinion comes from Peter Allison in his book “Whatever you do, don’t run: true tales of a Botswana safari guide”:

Any travel agent stresses to a client that they will be traveling in very small bits of motorized tin, and their luggage weight should reflect that. In fact, it is set at a strict twenty-five pounds. But looking at the camera bags and tripods being wrestled from the cargo area, I could tell that this guy had gone well over that.

Then, in mid-flight, he started taking photos, which was no problem, but when I pointed out some hippos, he leaned over the top of me and shoved me into the controls. Not one of them screamed when we went into a dive. What sort of people are they?

I like to think we’re not those sorts of people. I’m not too worried about interfering with pilots as I’m typically good at following most common sense rules, but the weight restrictions hit home. Just one of my several camera lenses I plan to bring weighs almost 4 lbs, or ~10% of my total limit. And this doesn’t include the monopod, computer, external HD, and other camera necessities. Uh oh. But luckily, I learn one of the perks of marriage: when Lindsey asks how much luggage we can bring, without hesitating, I turn and tell her 12 kg. I find myself an extra 3kg!

Allison, however, didn’t only scare me about how to prep, he also excited me about the things we might get to witness while there. And although most of his book detailed hilarious stories of tourists rather than inspiring tales of animals, this one stuck with me:

A great trumpet came from the elephants, as if in celebration, echoed by us on the vehicle, many of whom were in tears (and that unashamedly includes me). The baby sat looking bewildered at its ejection after twenty-two months in a comfortable womb, then started comical attempts to get up. Its ears were still plastered to the sides of its head, making it look like a squat sea lion, and it moved in the same humping legless manner.

After half an hour the baby stood, to more cheering from our vehicle. And it seemed to spawn a celebration from the elephants as well, as they started picking up dust and spraying themselves with it. This coats their skin and helps protect them from parasites, but each blast knocked the little baby down, and she (by now I had seen that it was a girl) struggled valiantly back to her feet and watched the enormous battleship-gray cruisers that were in a paroxysm of excitement around her.

Being in Africa will undoubtedly be humbling. We will almost always be the slowest and sometime even the smallest animal around. And yet in the end, some of our most primitive emotions will unite us all — excitement over a newborn, caring for one another, protecting one another, competing for resources and food, communicating and working together.

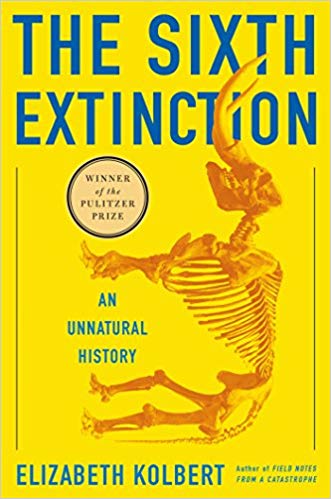

We’re prepared and excited to gain an appreciation for all animal species. A couple numbers to put ourselves in perspective: the human population nears 8 billion while the total wild lion population is estimated under 40 thousand, leopards under 15 thousand, cheetahs under 8 thousand. As Pulitzer Prize winner Elizabeth Kolbert writes about in “The Sixth Extinction”, there have been five mass extinctions over the last half billion years, and today, we’re currently seeing our 6th, which may be as devastating as when the asteroid impact ended the reign of the dinosaurs. I’m hopeful that the world can rebound again, but it may require its latest invasive species, homo sapiens, taking more of a backseat.