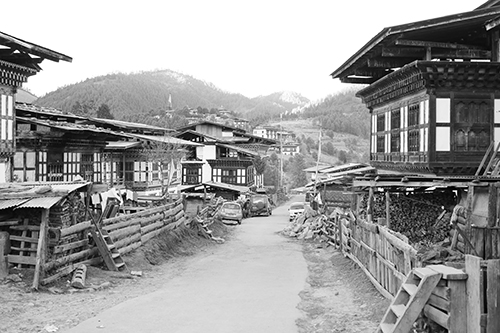

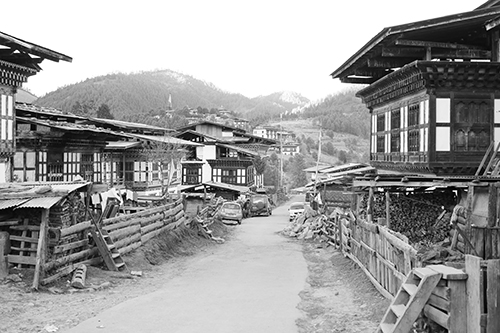

Before arriving to Gangtey, a three-hour drive from Punakha, our driver pulls over and our guide asks if we’d like to hike the rest of the way. It’s a welcome retreat from the bumpy dirt roads that takes us within feet of many yaks, grazing on the hillside. “Do people ever milk yaks?” we ask. “Yaks are quite difficult to milk,” Sonam tells us without a bit of mockery in his voice. We laugh, because of course they are. They’re huge animals with difficult temperaments. He tells us the fur from their underarms is soft and cut to make scarves, and the fur from their bodies is thick and coarse and used to make tents. Occasionally they’re eaten, and we’re in luck because it’s yak season. We talk and talk, until the mountain opens up and we feel like we’re in Switzerland, high above the earth with a perfect view of the valley below. Sonam points out our hotel in the distance, and we continue to walk, passing nuns collecting juniper along the way.

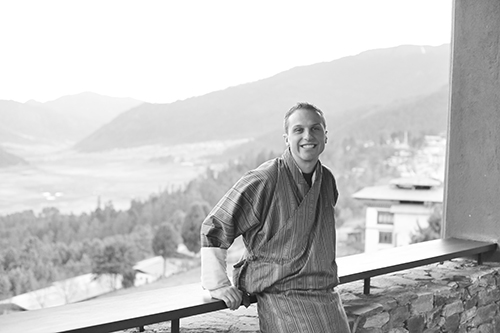

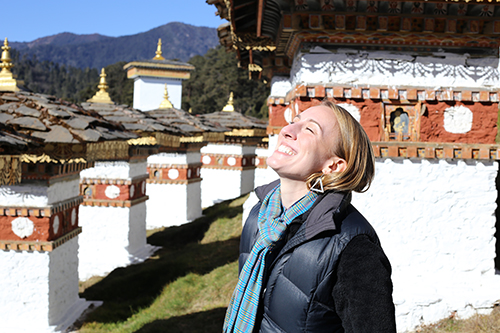

We’re elated by the time we arrive, and the joy continues to grow as we’re greeted with white welcome scarves, warm towels, and a welcome song sung by the entire staff against the incredible backdrop of the Gangtey mountains. The hotel manager gives us an orientation over delicious, warm cider then two women from the spa give us a complimentary welcome massage. We walk into our room where everything has been set up and are asked what time we’d like for them to light our fireplace. This is a welcome like we’ve never had before, and it immediately makes Gangtey Lodge feel more like a home than a hotel.

The food here is wonderful, and a welcome respite from the bowls of rice, fried vegetables, mystery meat, Chinese noodles, potatoes, chili and cheese sauce, and sometimes, inexplicably, pasta with red sauce that we’re served almost everywhere else. We do eat yak, favoring the yak burger best.

In the morning we head out for the run we’d promised ourselves we’d take every morning and almost at once are followed by the pack of dogs that Sonam had warned us about. We’re scared, slowing as to not antagonize them, knowing that the nearest hospital is over three hours away. As we approach the monastery, we consider climbing the steps to avoid them, but are happily surprised when they climb the steps instead, leaving us behind with the realization we have no rice to offer.

Outside, we try our hand at archery and darts. They’re impossible games, even with the shortened distance the hotel uses between targets. We hurl darts toward a tiny target and shoot an arrow toward a slightly larger board. We never make it, but our guides do. We later see a game of darts being played along the roadside and see the song and dance that both teams perform every time a target is hit. It makes us feel better about our lack of skill to know that a point is so valuable it deserves such ceremony.

Inside, we sit by the fire playing the cow and tiger game, a traditional Bhutanese game much akin to checkers played today only by farmers. We sip tea and wine and local craft beer and listen to the fire crack as we meet other friendly travelers. New Years comes and goes quietly this year, a few couples gathered around the fire counting down only to ourselves. There is no TV. No ball drop. No fireworks. It’s peaceful and warm and the magic of Bhutan is starting to seep into us.