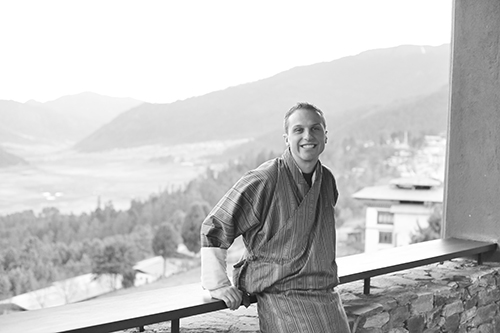

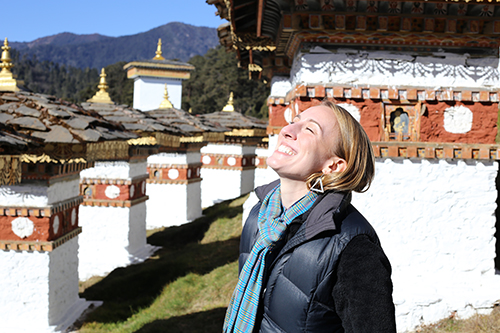

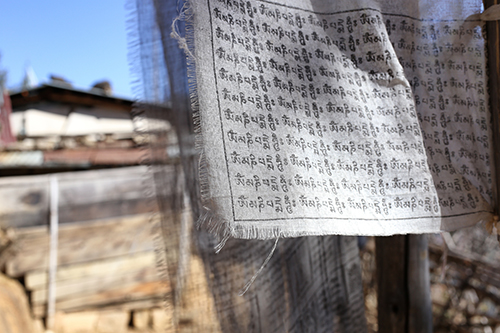

We are. Obsessed with happiness. Maybe that’s the problem. We define happiness as pleasure and triumph, and unhappiness as the lack of those things. And it turns out, we don’t skip down the street in complete joy all the time; in fact, we don’t do that most of the time, even in the metaphorical sense. Does that make us unhappy? Depends who you ask. In America, it kind of does. In Bhutan, it doesn’t. Bhutan’s happiness centers around a peace that comes form a state of well-being and contentment. Few people are in poverty. The children that are abandoned are placed in monasteries and nunneries and then elevated in social status as a result. Few are hungry. Education until university is free. Healthcare is free. Its landscape is beautiful; over 70% of the country is covered in trees. They’re proud of their country. Having only 700,000 people is helpful in all of this, but it really doesn’t seem too complicated.

When we ask Sonam why the country is so peaceful, he says it’s because people are content with what they have, and they do not envy each other. (Side note: this is partly achieved by aggressively kicking out the Nepalese back in the 80’s and by trying to postpone the inevitable invasion of western culture.) The grass might be green on the other side, but they’re also watering the grass that lives on their side.

And for one more insight on Bhutanese happiness, we turn to Eric Weiner in his book “The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World“.

“I would not have done anything differently. All of the moments in my life, everyone I have met, every trip I have taken, every success I have enjoyed, every blunder I have made, every loss I have endured has been just right. I am not saying that they were all good or that they happened for a reason…but they have been right. They have been okay. As far as revelations go it’s pretty lame, I know. Okay is not bliss or even happiness. Okay is not the basis for a new religion or self-help movement. Okay won’t get me on Oprah, but okay is a start and for that I am grateful. Can I thank Bhutan for this breakthrough? It’s hard to say … It is a strange place, peculiar in ways large and small. You lose your bearings here and when that happens a crack forms in your armor. A crack large enough, if you’re lucky, to let in a few shafts of light.”