Seoul is a blessing in disguise. Our time here is an accident, but Lindsey and I settle into our new reality and decide to make the most. We wake up Monday morning, ready to experience Seoul.

Breakfast: The concierge at our hotel helps us to chart a path for the day, starting with breakfast at a noodle shop tucked away in an alley in Myeondong. It’s the authentic feel we were craving. Old women work with plastic bowls in the back, their ingredients strewn in bags and hung in the alley. Locals come and go in the time it takes us to decide what to order. The food is spicy, delicious, and a steal at just $5 each.

Morning stroll: Although tea isn’t as big in South Korea as it is in some other Asian countries, we couldn’t resist green tea lattes from O’Sulloc Tea House. We sip slowly (they were… thick) as we wander the quiet main street Myeondong. This is the place to go for all Korean skincare products. Think masks made of snail mucus. The loud music blending together from each storefront is energizing. Along the way, we visit the Myeondong Cathedral, famous both for its Catholic significance and its advocacy of democracy. We round out our morning walk on the Cheonggyecheon, an urban park along the waterway that is unexpectedly decorated with some of the most playful and eccentric Christmas decoration.

Late morning pick-me-up: We find a piece of San Francisco when we step into Tesarosa Coffee near Gwanghwamun park. It has the hipster baristas, the expensive beans, the over-priced pastries, and the rustic yet modern décor. And for all of that, we love it! The coffee is great and we feel refueled and ready to continue.

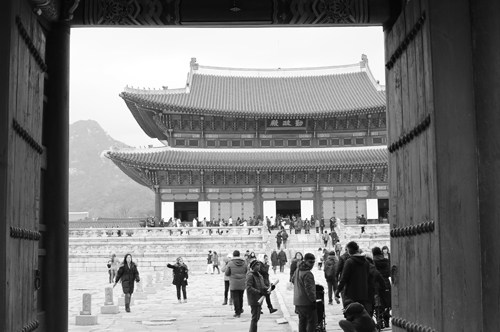

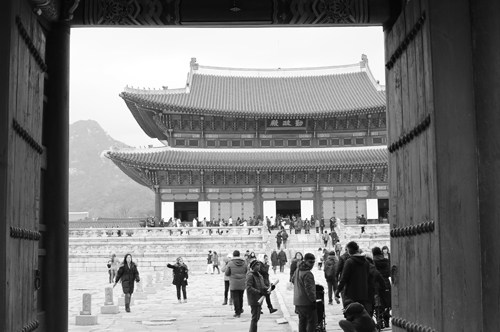

A piece of Korean culture: Gyeongbokgung palace is a beautifully restored palace in the north of Seoul. It is truly regal and beautifully restored. The sun comes and goes as we walk through the many levels of this palace, and each new corner presents us with more magical moments.

Lunch and afternoon shopping: After the palace, we head to Insadong, a part of Seoul with traditional shops and restaurants. We enjoy meandering through shops, looking at art in all of its forms from ceramic to paintings to sculptures. We sample dragon hair candy and buy a scroll that reads, “Every day is new”. It feels fitting given the circumstances. Bibimbap calls for lunch, so we find a spot called Gogung to rest.

A step back in time: With our stomachs full, we walk to Bukchon hanok village whose steep streets remind us of San Francisco. Each resident’s home is numbered, leading visitors along a path that offers a glimpse back in time. The beautiful roofs, the detailing on the doors and walls, and the window paneling all let us imagine what Seoul might have looked like many years ago. Highly recommend.

The other side of the river: So far today, we’ve explored the north side of the Han river, but to get a sense of Seoul, we can’t leave without exploring a new area. So we head to Garosugil near Gangnam, a tree-lined street full of up-scale shops and restaurants. It’s Boston’s Newbury Street in South Korea. One store called Line Friends is drawing a real crowd, so like any good tourists, we also venture in. We don’t know exactly who these friendly looking characters (stuffed animals) are, but we still hold a photo shoot with an extremely oversized bear to commemorate this occasion.

Dinner time: Exhausted, we end our day with some Korean BBQ at Two Plus (TwoPpul DeungShim). The beef that we have is incredible, and by definition straight off the grill.

Evening markets: We thought this night was done until we saw flashing lights from the other side of our hotel. We wandered over, slipping under the streets and through the metro to reach the place where we’d started our day: Myeondong. This time, Myendong was alive with dozens of street vendors selling juice, fried shrimp, and Korean snacks. The street seemed to be brighter at night than it was during the day.

And with that, we call it a day. 36 hours well spent in Seoul, South Korea.