After Mdina, a tiny town of 300 people that completely empties every night around 5pm, Valletta feels like a true metropolis (kinda). There are restaurants and bars, shops that stay open late, theaters, and seemingly hordes of people.

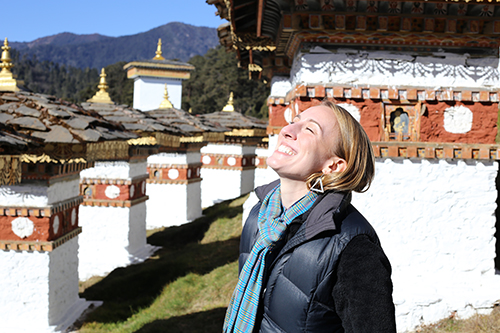

Stomachs still full a couple days later from our Christmas dinner, early breakfast, regular breakfast and lunch, we find a small wine bar named Trabuxu serving snacks for tonight’s dinner. The wine is great, the local cheese peppery, and the service accommodating enough for Lindsey to find things to eat that are neither alcoholic nor unpasteurized. We sit outside on a little stoop people watching as we enjoy our light-ish meal.

Our first full day in Valletta is definitely full. We start with a hotel breakfast followed by a wonderfully orienting tour of the old city. The guide helps us continue to piece together many parts of Malta’s history through the different kingdoms that once ruled. But two of the highlights extended beyond just listening to the stories but actually touching and witnessing them.

What better way to touch history than turn the pages of a 400 year book! Lindsey and I both look at each other a couple times before building up the courage to turn one of these ancient pages. One of the books we flip through contains the history of Malta, another was handwritten and has interspersed little drawings. The Valetta Library holds works dating as far back as 1100, but don’t worry, that one was well protected and far out of our hands.

We next get to witness a bit of history as we enter a 5th-generation gilder’s studio. The pride he takes in his work has likely only grown through the generations. He is in the process of making a Maltese clock for his daughter’s recent wedding gift and he explains the process of how the gold is gilded onto the frame. Each smaller-than-one-millimeter thick square of gold is several Euros, and the clock he’s in the middle of building could reach up to 10,000 Euros. He uses all traditional methods including natural glues made from animals. The only new technology that he’s incorporated into his practice is that of air conditioning – this allows him to work year around even during the humid months.

We round out our day of touring by going to an ornate theater in the middle of town where they’re currently performing a very silly rendition of the Little Mermaid. These satirical plays, full of their British humor, are an end-of-year tradition. Otherwise, the theater typically is home to a bit more serious material. That said, it’s wonderful to see all of the locals performing and their families in the audience cheering them on. When surrounded by so many tourists around town, it was wonderful to see this strong local community as well.

Although Valletta does not charm us as much as Mdina did, it did give us an even greater appreciation for the history of the island. Every site we visit from Fort St. Angelo to St. John’s Cathedral which houses the largest Caravaggio to the Barrakka Gardens all reinforce that so much has happened on such a small piece of land.

Leading up to and throughout our visit, I’ve been enjoying The Sword and the Scimitar, a book by David Ball that captures through a tale of historical fiction the period when the Order of the Knights of St. John ruled on the island. Many of the names that appear in the book are also said aloud by our tour guide and in many of the museums we walk through. Although at times a little violent, the book was a very entertaining way to learn a piece of history of this special island. And what better way to enjoy some of this book than with a cup of joe from our favorite coffee shop Lot Sixty One Coffee Roasters, which I think we averaged two visits per day.