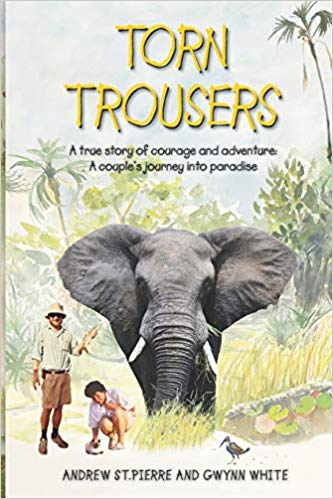

Several very long flights later, our excitement for the trip only grows. To get ourselves mentally prepared for the adventure to come, we read a comical book by Andrew and Gwynn, a couple who become managers of a game lodge in the Okavango. From hearing their stories of all that goes wrong at the lodge from destructive baboons and hyenas to threatening elephants to never receiving enough shipments of food to disturbing an angry wasp nest and so much more, we’re now prepared to call any mishap just another part of the adventure. One of the wilder things, though, is how much goes on behind the scenes at these lodges for which the guests have no idea. And so we’re also excited that there’s a non-zero chance that we unknowingly participate in some of these “matatas” (meaning problems in Setswana).

In addition to enumerating their matatas, Andrew St Pierre and Gwynn White also share their love for the region in the below quote as part of their larger story in

Torn Trousers: A True Story of Courage and Adventure: How A Couple Sacrificed Everything To Escape to Paradise.

“There was a place so tranquil that angels went there to rest. It was a place of such singular beauty, even the lilies dressed for dinner. Yet the ebb and flow of its life-giving water was determined by a climate a thousand miles away. The water level was high during times of drought and low in times of rain. At its heart ran a river that sought the sea but never found it. Instead, it spilled onto a plateau of sand, spreading like an Eden across the desert until at last it vanished into the dust.

Animals, great and small, followed the river, each in pursuit of happiness. When they found it, they stayed. Fish swam in quiet eddies. There were birds so varied in hue they confused the rainbows. Vast herds of elephant, buffalo, and antelope made homes here, and behind them carnivores trod. Trees offered shelter to snakes and comfort to travelers.

This was where my heart lay, in the Okavango Delta in northern Botswana.”